Weird Wisconsin: The Bill Rebane Collection LE Blu-ray Review

- Gabe Powers

- Jun 15, 2021

- 14 min read

Arrow Films

Blu-ray Release: May 25, 2021

Video: 1.33:1 & 1.85:1/1080p/Color and Black & White (Monster A Go-Go only)

Audio: English DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 Mono

Subtitles: English

Run Time: 638+ minutes

Director: Bill Rebane

There exists a (mostly) agreed-upon pantheon of Masters of American Horror Cinema, ranging from silent era greats and independent mavericks, to the superstar directors of the ‘70s, ‘80s, and modern era. Beneath the prestige of the Lon Chaneys, Roger Cormans, and George A. Romeros are the Masters of American Trash Cinema – purveyors of zero-budget junk that nonetheless earn ardent cult followings, due to the industriousness, their eccentricities, and the uniqueness of their specific artistic visions. Among names like Al Adamson, Andy Milligan, Ted V. Mikels, Frank Henenlotter, Herschell Gordon Lewis, and, of course, Ed Wood Jr., is a Latvian-born, self-starter named Bill Rebane, who built his own film studio on a farm outside the small town of Gleason, Wisconsin.

Disc One:

Monster A Go-Go

American astronaut Frank Douglas returns to earth as a ten-foot-tall radioactive humanoid monster! (From Arrow’s official synopsis)

Rebane’s first feature was an unfinished patchwork Z-movie known as Monster A Go-Go (1965). Remembered by everyone from Mystery Science Theater 3000 cast members to Rebane himself as one of – if not the worst movie of all time, Monster A Go-Go was shot under the title Terror at Halfday, abandoned, and bought by Herschell Gordon Lewis himself, who padded it out with additional footage, creating a new a brain-melting combination of both filmmakers’ weirdest and worst tendencies. Sadly, Monster A Go-Go is genuinely as bad as its reputation suggests. Like all truly terrible cult films, it’s a boring chore to sit through, especially without the benefit of mind-altering substances, a roomful of rowdy friends, or sarcastic commentary from a couple of TV robots. Any joy must be gleaned from the baffling bad choices Rebane made and the half-decent cast’s struggles against the script. I personally come to Monster A Go-Go as a fan of Lewis’ brand of schlock and find it fascinating in theory as possibly his laziest attempt at filmmaking. Lewis was always honest about being in the industry for monetary, not creative rewards. But, in most cases, no matter how half-assed his work was, it was still, technically, work.

Every movie in this set has been newly restored from “the best surviving film elements,” similar to their H.G. Lewis Feast Blu-ray set, though none of the materials here are in as dire of shape as those Arrow was forced to use for that collection (it helps that there are fewer movies here). Monster A Go-Go is presented in its original black & white, 1.33:1 aspect ratio, and 1080p. A 16mm print was scanned in 2K at Company 3. It was graded and restored at R3Store Studios in London. I feel pretty comfortable saying that this is the best this movie will ever look. It was largely shot by someone who didn’t know what he was doing, it was rescued from the trash by someone known for his color photography (Lewis), and it has been through the drive-in and home video ringer for decades now. Presumably a negative source would be better (it’d probably have fewer prevalent vertical scratches), but the harsh contrast and soft edges actually make Frank Pfeiffer’s amateur photography appear somewhat moody. At least moodier than budget VHS releases did. The original mono soundtrack was taken from the print source and is presented in 1.0 DTS-HD Master Audio. It’s muffled and flat, but no more than expected for such a famously badly mixed movie – to the point that much of the original audio was unusable. The Other Three’s original music and Lewis’ added narration are pretty much the two elements that you don’t have to struggle to hear.

Invasion from Inner Earth

In the Canadian wilderness, a group of pilots listen to reports of planes crashing, cars stalling and a deadly plague gripping the planet. As it becomes clear that the Earth is amidst an invasion, they barricade themselves in a cabin in the woods and wait for impending doom. (From Arrow’s official synopsis)

Nearly a decade after shooting his part of Monster A Go-Go, Rebane made his second movie, Invasion from Inner Earth (1974, filmed in 1972). Because it has early versions of the hallmarks that later defined his specific style – not to mention the fact that he actually finished it himself – it feels like his official coming-out party. Though frustratingly uneventful, Invasion from Inner Earth at the very least has a sense of experimentation. When not dragging the audience through the boring bickering fits between the small town boys battling the very slow invasion, Rebane picks interesting camera angles, lights his sets colorfully, and makes attempts at flashy kaleidoscopic editing and in-camera effects. His weirdest choices resemble something like atmosphere. The wintery locations and limited cast also convey a sense of isolation that stands in for actual scares (he did this better in later films – see below). The problems this time aren’t tone or really even technical execution, but pacing or lack thereof. It’s worth noting that Invasion from Inner Earth has a striking similar ending to Alex Proyas’ Knowing (2009).

Invasion from Inner Earth is presented in its original 1.33:1 aspect ratio and 1080p. A 16mm print was scanned in 2K at Company 3. It was graded and restored at R3Store Studios in London. This time, working from a 16mm print has caused some issues with overall clarity. Everything is generally mushy. That said, it’s basically impossible to tell which artifacts are an issue with the materials and which are simply part of Jack Willoughby’s strange, foggy, lens-trick-heavy photography. There aren’t any problems with notable print damage or digital compression and the transfer reproduces those specifically pastel-tinged 16mm colors well. The 1.0 mono soundtrack is presented in DTS-HD Master Audio. The track is stronger than the Monster A Go-Go track (what wouldn’t be?) and has no issues with crackle or pop, but is still quite muffled. The catalog music is nice and effective, though. I’m especially fond of the all-keyboard rendition of Ennio Morricone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) title theme.

Extras

Straight Shooter: Bill Rebane on Monster A Go-Go! (10:46, HD) – In the first of six newly recorded director interviews, Rebane recalls struggling to complete the film, running out of funding over and over again, almost casting Ronald Reagan, and handing things off to Lewis.

Straight Shooter: Bill Rebane on Invasion from Inner Earth (9:58, HD) – Rebane discussing the making of his first Wisconsin-shot feature, lost footage, and enjoying the total freedom of the completely independent movie.

Kim Newman on Bill Rebane (15:07, HD) – The author of Nightmare Movies: Horror on Screen Since the 1960s (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011) compares Rebane to indie genre auteurs from other US states and breaks down most of his filmography.

Bill Rebane short films:

Twist Craze (1961; 8:49, HD) – A mini-movie inspired by the ‘60s dance craze known as The Twist.

Dance Craze (1962; 14:41, HD) – After Twist Craze proved successful, Rebane made this short subject follow-up.

Kidnap Extortion: Robbery by Telephone (1973; 14:28, HD) – A step-by-step docudrama reenactment of a kidnap-extortion bank robbery, which I guess was a problem in the ‘70s?

Stills and promotional gallery

Disc Two

The Alpha Incident

A space probe returns from Mars carrying a deadly organism that could destroy all life on Earth! While being transported across the country by train, the micro-organism is accidentally released, resulting in the quarantine of an entire train station. Those trapped inside must wait for the government to find a cure while trying not to sleep, because that’s when the organism strikes! (From Arrow’s official synopsis)

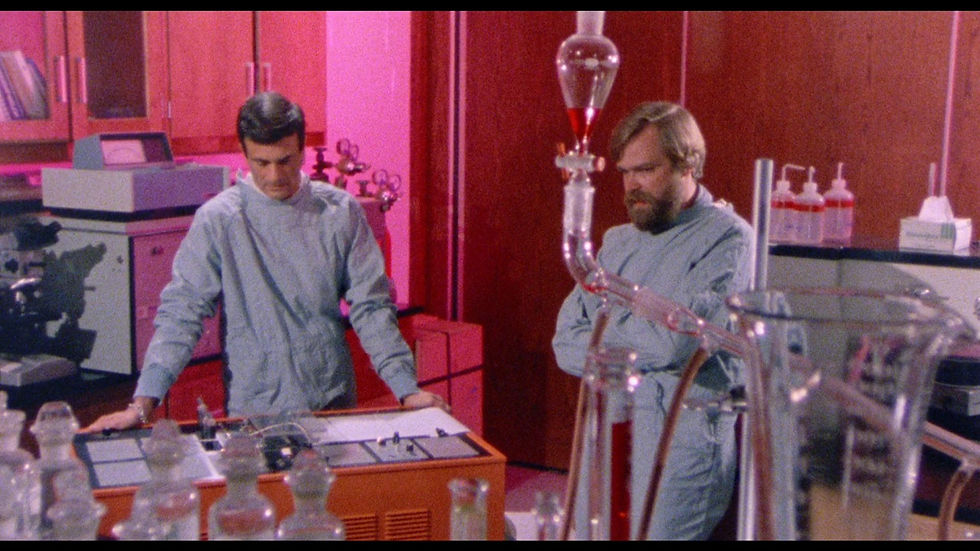

Following the success of his most popular film, The Giant Spider Invasion (1975), Rebane made a relatively conventional sci-fi thriller called The Alpha Incident (1978). I imagine the main inspirations were Robert Wise’s 1971 adaptation of Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain and Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). Knowing he couldn’t match those studio-financed production values, Rebane built upon filmmaking (and story) ideas he’d already experimented with during Invasion from Inner Earth, once again utilizing the rural Gleason locations to convey a sense of isolation and amplify tension. Pacing continues to plague the otherwise naturalistic drama and reliable performances occurring between amusing sci-fi/horror shenanigans (the gory exploding brain bit is pretty cool), but what’s interesting this time around is that you can plainly see which scenes bored Rebane. While certain sequences are cleverly shot and uniquely edited (Rebane acted as his own editor here), others are impossibly flat and drone on endlessly. I hesitate to call it a good movie, but Alpha Incident has all the distinguishing characteristics of a “real” movie and an impressively bleak, Romero-esque ending, which is more than we can say for a lot Rebane’s work (for comparison, he followed Alpha Incident with two of his silliest and most Rebanesque movies – The Capture of Bigfoot [1979] and, my personal favorite, Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake [1981]). Additionally, it’s about rural Wisconsinites refusing to remain in quarantine after being exposed to a deadly virus, so there’s definitely some contemporary appeal (the documentary on disc four reveals that Rebane himself posted conspiracy theories about Chinese-infected toilet paper spreading COVID-19 on his social media, which is just perfect).

The Alpha Incident had the fortune/misfortune of being included on more than one of budget label Mill Creek’s 50-movie DVD packs, meaning that it has been more readily available than Rebane’s other films, but also looked consistently like garbage. This new 1.85:1, 1080p transfer was taken from 35mm dupe negative, scanned in 2K, graded, and restored at the American Genre Film Archive (AGFA). The image is stronger than the previous two transfers, likely due to the negative source, including tighter details, finer grain, and punchier colors (the 35mm source might also explain the upgrade). The grain has an occasional dirty or snowy quality and some scenes exhibit print damage, but the gritty appearance fits the film. AGFA also restored the original mono soundtrack from a 35mm print source in-house and it is presented in uncompressed DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0. This mix is a big improvement on the first two films with broader dynamic range and more complex layering; however, dialogue hiss is present and the sound quality varies from shot to shot, depending on location audio or ADR usage.

The Demons of Ludlow

The population of a small, quiet town prepares to celebrate the bicentennial anniversary of its founding, but the town of Ludlow has a very dark past and, when a piano arrives at auction, the ghosts of its past return to seek retribution. (From Arrow’s official synopsis)

It turns out that what at first appears to be the most unique horror movie in this collection might have actually been a plate of art-house-turned-trash-house Ulli Lommel’s leftovers. The Demons Of Ludlow (1983) was shot using locations, sets (both from Rebane’s ranch), and some cast members from Lommel’s The Demonsville Terror (1983), but replaces that film’s vengeful witches with a hideous piano that is haunted by, um, horny colonial era aristocrats(?). Regardless of whatever he was attempting to do (critics have noted many specific similarities to John Carpenter’s The Fog [1980]), the director’s strangely anachronistic instinct to combine gruesome set-pieces with desperately dated images of household objects floating on fishing lines works in his favor this time. The Demons of Ludlow feels like a real contender for the American underground horror canon, alongside other peculiar haunted object oddities, like George Barry’s Death Bed: The Bed that Eats (1977). The photography, credited to Rebane himself under the pseudonym Ito, is startlingly evocative at times. Again, there are clearly sequences he wasn’t particularly interested in shooting, but the gonzo horror moments are lit like a budget Mario Bava movie (there’s even one shot I’m almost certain he stole from Kill, Baby, Kill! [Italian: Operazione paura; aka: Operation Fear, 1966]). The so-bad-it’s-good crowd will find more dopey lines and ridiculous situations to giggle at (the piano sounds like a Casio keyboard for some reason) and cult horror fans, like myself, will appreciate an abatement of Rebanesque filler.

Company 3 scanned 35mm color reversal intermediate (CRI) elements of Demons of Ludlow, then the transfer was graded and restored at R3Store Studios in London. The 1080p, 1.85:1 image is sometimes slightly muddy, but I suspect this has more to do with Rebane’s original photography than the condition of the elements or restoration process. My biggest clues are that the bright green & blue optical effects don’t appear muddy and, while the darkest sequences are particularly snowy, this grit doesn’t otherwise get in the way of the brightly lit scenes or those wonderful green and pink gels. Black levels are stronger than the previous three transfers and don’t crush the neutral hues too much. Demons of Ludlow is presented in its original mono sound, taken from the optical negative, in DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0. This is another step up in quality, probably thanks to upgraded tech at the Gleason ranch. The mix is still simple, usually either dialogue or music-driven, depending on the scene, but there are no big dips in volume/clarity, little hiss distortion, and Ric Coken & Steven Kuether’s score has plenty of range.

Extras

Straight Shooter: Bill Rebane on The Alpha Incident (9:24, HD) – The director calls The Alpha Incident his first real feature and recalls the casting and writing processes, special effects limitations, and maintaining control over the production.

Straight Shooter: Bill Rebane on The Demons of Ludlow (7:44, HD) – In the fourth of this six-part series, Rebane talks about working on his new soundstages, building the storyline around the piano (which he already owned), and self-distributing. He also (playfully?) accuses Ulli Lommel of plagiarizing one of his unfilmmed scripts for Demonsville Terror.

Rebane’s Key Largo (16:05, HD) – In this new visual essay, historian, critic, and programmer Richard Harland Smith breaks down The Alpha Incident, from its influences, through Rebane’s earlier work, the careers of its cast (fellow Midwesterners will be delighted to learn that the briefly featured Ray Szmanda went on to become the Menards Guy), its release (it was double-featured with Star Wars), and its status as an unlikely COVID-19 parable. Ultimately, he compares it to John Huston’s bottle-episode classic Key Largo (1948), hence the title, but he also draws comparisons it and Rebane’s other sci-fi movies, Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) and The Crazies (aka: Code Name: Trixie, 1973), The Andromeda Strain, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, George P. Cosmatos’ The Cassandra Crossing (1976), and John Sturges’ The Satan Bug (1965).

The Alpha Incident trailer

The Demons of Ludlow trailer

Stills and promotional gallery

Disc Three

The Game

Three bored millionaires gather nine people at an old mansion to play “The Game” …if they can meet and conquer their fears and they’ll receive a million dollars in cash. But all is not as it seems! (From Arrow’s official synopsis)

For The Game (aka: The Cold, 1984) Rebane and screenwriters William Arthur & Larry Dreyfus started with a tried & true high concept base that lends itself well to a small budget and limited sets/locations. The “make it through the night and win money” thing worked for The Cat and the Canary (1922) and House on Haunted Hill (1959), why wouldn’t it work for Bill Rebane? As a purposeful black comedy, The Game has a lot more to prove than Monster A Go-Go or Demons of Ludlow, which get by on accidental giggles. I find that Rebane’s sense of humor doesn’t jibe well with my own and that many of his earnest attempts at comedy fall flat, whereas any earnest attempt at setting the mood made me laugh. Rebane’s not a fool, though, so it’s difficult to know for sure that I wasn’t laughing at intended ironies (surely the barfing worm monster was meant to be funny, right?). The funniest thing about the film is the fact that the three bored millionaires look very much like they’re being outfitted by a film crew with a sub-million-dollar budget. They dress shabbily and, despite the misnomer in the official plot description, they don't hang out in a mansion, but a two star hotel that Rebane could rent for almost no money, because it was going out of business. Technically speaking, Rebane continues rushing through exposition and other filler, while putting a little more effort into the patently absurd horror scenes.

The Game is presented with the option of 1.85:1 and 1.33:1 aspect ratio, though this review will pertain mostly to the 1.85:1, 1080p image. This time, the original 16mm AB camera negative was scanned in 2K by Company 3, then graded/restored by AGFA. Despite the 16mm source leading to a heck of a lot of heavy grain, this may be the best transfer in the set, simply because it’s such a good representation of the footage. The notable issue are intermittent streaks of mold or emulsion on the left edge of the screen. The colors are exceptional, especially acrylic costume/set design and the vivid red and green lighting used during “scary” moments. The original mono sound was remastered from the track negative and is presented in DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0. The Game is another case of the audio quality being at the mercy of the crew’s technical prowess. Some scenes sound just fine – equal to a typical straight-to-VHS horror movie – while others are recorded so poorly that the dialogue fades almost into the background. Things are most consistent when Rebane opts for ADR and canned effects. The bloopy synth music is credited to Bruce Malm and set alongside a load of copyright-free catalog material.

Twister’s Revenge

Three bumbling criminals repeatedly attempt to steal the artificial intelligence control system of Mr. Twister, a talking Monster Truck, by kidnapping its creator. (From Arrow’s official synopsis)

Apparently, Rebane didn’t particularly like making horror movies and sort of resented his role as a horror filmmaker. The fact that he was particularly bad at horror was the first clue, I suppose. Anyway, the final movie in this collection is beloved goofball action-comedy Twister’s Revenge (1988). Even while trying to avoid horror, Rebane still managed to make a monster movie – a monster truck movie (yuk yuk yuk). Ever behind the times by at least five years, Rebane appears to have been trying to cash-in on the recently canceled talking car series, Knight Rider (1982–’86), by combining it with the raw vigilante justice of Death Wish (1974), all while using the tone of the also recently canceled redneck criminal comedy series, Dukes of Hazzard TV series (1979-’85). Regrettably, to really pull off this admittedly amusing combination, a director really needs a measure of filmmaking control over comedy and action, and Rebane isn’t much better at either of those than he is at horror. Despite the jokes not landing and the action being utterly lethargic (credit where it is due: a lot of buildings and cars are demolished), the baffling premise of an intelligent monster truck hunting down Three Stooges-caliber criminals and the speedy (for Bill Rebane) tempo make Twister’s Revenge surprisingly easy to watch. The parts not relating to the robo-truck are also a bluntly honest time capsule of rural Wisconsin hickdom during the mid-’80. In these terms, it’s essentially a documentary.

From what I can surmise, Twister’s Revenge might be the holy grail of this set. It has a substantial following and has never been available on decent home media before. It was released straight-to-video VHS via a local Wisconsin company, then dumped onto another Mill Creek 50-movie DVD collection. This Blu-ray was sourced from a 35mm print, which was scanned in 2K at Company 3, and is presented in 1080p and 1.85:1. Most of the problems relate directly to the print source, which leads to some fuzzy details, crushy shadows, and lumpy grain. Otherwise, the image has been respectfully cleaned (some sequences are rougher than others) and the colors are relatively vibrant for an old, cheaply made print source. It’s a monumental upgrade over Mill Creek’s non-anamorphic, VHS-derived disc. The original mono sound is presented in 1.0 DTS-Master Audio and, once again, I assume the problems pertain to the source material. This mix is particularly compressed, making for a flat and mumbly experience. There’s also the issue of overlapping elements canceling each other out, ADR inconsistencies, pitch shifts, and sudden dropout – all stuff Company 3 and Arrow can’t fix without a massive audio overhaul. M. Hans Liebert’s rock-synth score fares the best, overall.

Extras

Straight Shooter: Bill Rebane on The Game (6:57, HD) – The director talks about his “brain fart” of a script, living on location in the hotel, and making what he thinks was his all-time lowest-budget movie.

Straight Shooter: Bill Rebane on Twister's Revenge (8:10, HD) – In the last of the Straight Shooter interviews, Rebane recalls building a story and action around the truck’s availability, renting tanks for the climax, and finding places around Wisconsin in need of demolition.

Discovering Bill Rebane (28:16, HD) – Comic book artist, author, and horror movie historian Stephen R. Bissette discusses his personal connection to Rebane’s work film-by-film and the importance of regional cult filmmaking in America, specifically from a fan that grew-up outside of Wisconsin (in Vermont, to be precise).

The Game trailer

Twister’s Revenge trailer

Stills and promotional gallery

Disc Four

Who is Bill Rebane? (115:18, HD) – An Arrow exclusive, damn-near definitive feature-length documentary directed by historian/critic David Cairns, featuring interviews from filmmakers (including the subject of Chris Smith’s American Movie and fellow Wisconsinite Mark Borchardt), fans, historians, critics, and the cast and crew who worked with Bill Rebane. Who is Bill Rebane? is stylishly produced and edited, despite limited resources (some interviews were conducted during quarantine), and info-packed, covering the director’s entire career and leading to surprisingly little overlap with the other interviews and featurettes included with this collection. Most importantly, it is entertaining, which isn’t something we can say about all retrospective cult movie docs, even the extremely informative ones.

King of the Wild Frontier (93:39, HD) – Another, much longer conversation with Stephen R. Bissette (essentially the long version of the same interview used for Discovering Bill Rebane and Who is Bill Rebane?).

Outtakes – Invasion from Inner Earth (16:42), The Alpha Incident (11:12), and The Demons of Ludlow (9:41)

The Giant Spider Invasion trailer

Behind the scenes stills galleries – A Rebane Miscellany, The Giant Spider Invasion, The Capture of Bigfoot, Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake, Blood Harvest, and from the collection of Stephen R. Bissette/Spiderbaby Archives.

Limited Edition box contents:

Fully illustrated 60-page collector’s booklet featuring new essays by historian and critic Stephen Thrower, author of Nightmare USA: The Untold Story of Exploitation Independents (FAB Press, 2007)

Reversible poster featuring newly commissioned artwork by The Twins of Evil

The images on this page are taken from the BD and sized for the page. Larger versions can be viewed by clicking the images. Note that there will be some JPG compression.

Komentáře